Puerto Rico: When It Rains, It Pours

✑ MICHAEL ROBERTS | 2,265 words

Hurricane Maria left Puerto Rico devastated, but "Puerto Rico was faced with bankruptcy even before the hurricane". The root causes of Puerto Rico's economic weakness; a story of predatory vulture funds, tax scams of multinationals and a US-dominated monitoring body (PROMESA) whose plan (austerity), in the words of economist Joseph Stiglitz, "makes a recovery a virtual impossibility".

Michael Roberts, a marxian economist and author, works in the City of London as an economist and has written extensively on economic crises from a marxian perspective. He has published several books including his most recent The Long Depression; Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism (2016) published by Haymarket Books. In recent years, his blog The Next Recession has reached an international audience.

Originally published on Roberts' blog The Next Recession on October 17, 2017.

‟A small island exploited – all at the encouragement of foreign investment banks making huge fees.

Hurricane Maria left Puerto Rico devastated, but "Puerto Rico was faced with bankruptcy even before the hurricane". The root causes of Puerto Rico's economic weakness; a story of predatory vulture funds, tax scams of multinationals and a US-dominated monitoring body (PROMESA) whose plan (austerity), in the words of economist Joseph Stiglitz, "makes a recovery a virtual impossibility".

Michael Roberts, a marxian economist and author, works in the City of London as an economist and has written extensively on economic crises from a marxian perspective. He has published several books including his most recent The Long Depression; Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism (2016) published by Haymarket Books. In recent years, his blog The Next Recession has reached an international audience.

Originally published on Roberts' blog The Next Recession on October 17, 2017.

▰

When it rains, it pours. Hurricane

Maria hit the island of Puerto Rico off the US mainland leaving the

country devastated with no power, no food and water.

Puerto Ricans are US citizens, as the

island is officially a ‘US territory’ – in effect, a colony

like the French overseas territories. But the US mainland

authorities did little to help and, when they did, it was inadequate.

Power remains lost; homelessness continues and President Trump

visited the most well-off part of the island to hand out paper towels

– to mop up no doubt!

But even before the hurricane, Puerto

Rico’s 3.5m people were in a parlous state. It had become a

graphic example of what capitalism and colonial rule can do in

exploiting resources and people, through distortions of the local

economy and corruption of local and foreign institutions.

Puerto Rico was faced with bankruptcy

even before the hurricane. By bankruptcy, I mean that the public

sector debt of the island had reached astronomical levels, making it

impossible for the island government to service the debt and thus

facing default on its bonds owned by local and foreign institutions

(mainly hedge funds).

How did this come to pass? Throughout

the modern economic history of Puerto Rico, one of the central

drivers of its economic growth has been the US tax code. For

over 80 years, the US federal government granted

various tax incentives to US corporations operating in Puerto Rico.

Most recently, beginning in 1976, section 936 of the tax code granted

corporations a tax exemption from income originating from ‘US

territories’. US corporations benefited greatly from locating

subsidiaries in Puerto Rico – a ‘rich port’ indeed. Income

generated by these subsidiaries could be paid to US parents as

dividends, which were not subject to corporate income tax.

Puerto Rico thus became a large tax

scam for multi-nationals. The main ‘exporters’ to Puerto Rico

were pharma and chemical companies in Ireland, Singapore and

Switzerland. Thus Puerto Rico imported pharmaceutical ingredients

from low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland and then exported finished

pharmaceuticals to high-tax jurisdictions in Europe and the US.

“Specifically, PR

runs, on paper, a huge trade surplus in pharmaceuticals – $30

billion a year, almost half the island’s GNP. But the pharma

surplus is basically a phantom, driven by transfer pricing: pharma

subsidiaries in Ireland charge themselves low prices on inputs they

buy from their overseas subsidiaries, package them, then charge

themselves high prices on the medicine they sell to, yes, their

overseas subsidiaries. The result is that measured profits pop up in

Puerto Rico – profits that are then paid out in investment income

to non-PR residents. So this trade surplus does nothing for PR jobs

or income.”

This booming economy raised little tax

revenue. So Puerto Rican governments borrowed to provide public

services rather than tax multi-nationals. Due to these extensive tax

credits and exemptions, Puerto Rico lost out on $250-500 million a

year in revenue. It did this for four decades, encouraged by

financial consultants. Soon it entered the realm of Ponzi-financing,

namely, issuing debt to repay older debt, as well as refinancing

older debt possessing low interest rates with debt possessing higher

interest rates.

Then disaster happened. In the US,

section 936 became increasingly unpopular throughout the early 1990s,

as many

correctly saw it as a way for large corporations to avoid taxes.

Ultimately, in 1996, President Clinton signed

legislation that phased out section 936 over a

ten-year period, leaving it to be fully repealed at the beginning of

2006.

Without section 936, Puerto Rican

subsidiaries of US businesses were subject to the same worldwide

corporate income tax as other foreign subsidiaries. They fled the

island. Between 1996 and 2006, the US Congress eliminated the tax

credits, contributing to the loss of 80,000 jobs on the island and

causing its population to shrink and its economy to contract in all

but one year since the Great

Recession.

At first, the Puerto Rican government

tried to make up for the shortfall by issuing bonds. The government

was able to issue an unusually large number of bonds, due to dubious

underwriting from financial institutions such as Spain’s Santander

Bank, UBS

and Citigroup.

According to a report from Hedge Clippers, Santander issued almost

$61 billion in bonds from the Puerto Rican government through

subsidiaries that served as municipal debt underwriters, obtaining

$1.1 billion in fees in the process.

Santander officials were also officials

of the Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank. Thus Santander

officials in the Development Bank decided whether to issue debt for

Puerto Rico and then arranged that Santander should pocket the fees

for organising the bond issues! They also decided that sales tax

revenue that should have gone to the government should be siphoned

off to service COFINA (PR Sales Tax Financing Corporation) bonds.

They even assigned government employees’ pension contributions to

pay for bond issues.

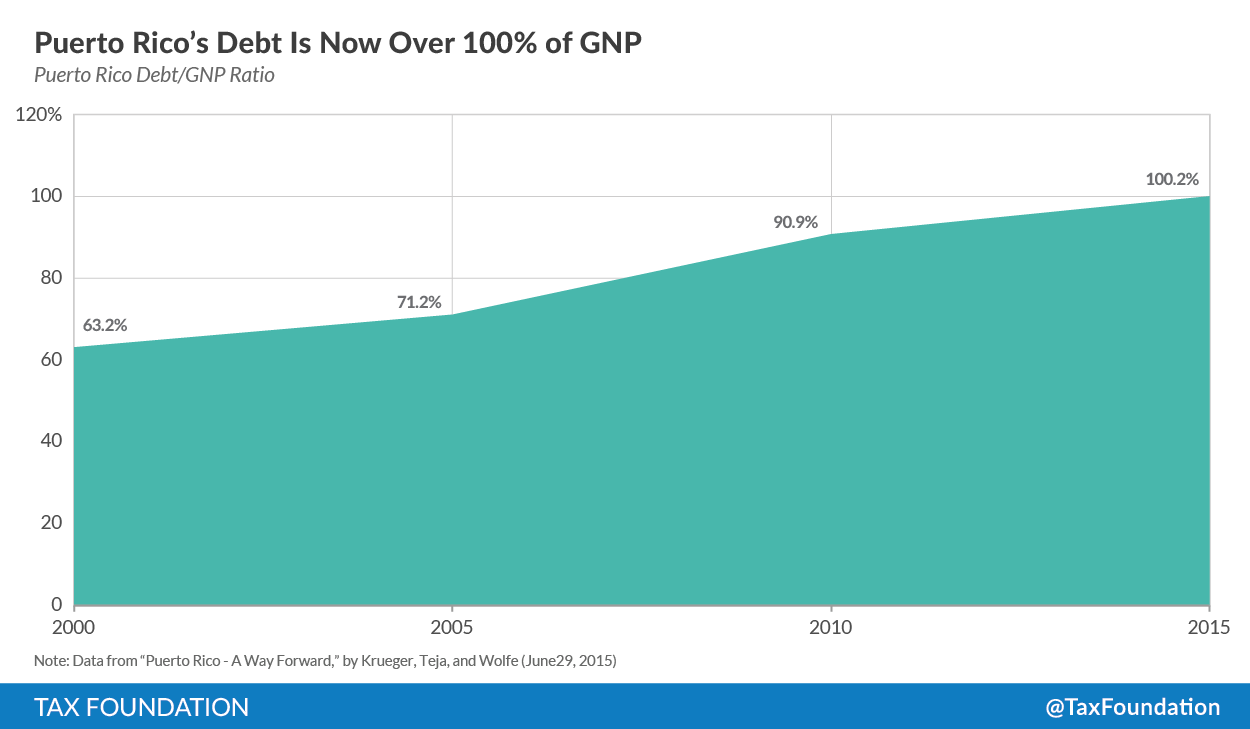

Not coincidentally, 2006 also marked

the beginning of a deep recession for Puerto Rico, which has lasted

until today. Between 2000 and 2015, Puerto Rico’s debt rose

from 63.2% of GNP to 100.2% of GNP. Eventually the debt burden became

so great that the island was unable to pay interest on the bonds it

had issued. Puerto Rico’s $123 billion liabilities from debt ($74

billion) and unfunded pension obligations ($49 billion) are much

larger than the $18 billion Detroit

bankruptcy.

The tax regime remains paralysed. The

Department

of Treasury of Puerto Rico is incapable of collecting

44% of the Puerto

Rico Sales and Use Tax (or about $900 million).

Public spending is also distorted. A public teacher’s base salary

starts at $24,000 while a legislative advisor starts at $74,000. The

government has also been unable to set up a system based on

meritocracy,

with many employees, particularly executives and administrators,

earning large salaries while health workers struggle.

The Puerto

Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) provides free

electricity to local governments. The utility had

improperly given away $420 million of electricity and that the

island’s governments were $300 million delinquent in payments. As

a result, PREPA had no funds to invest in new technology and built up

a debt of $9 billion. In

2012, the Puerto Rico Ports Authority was forced to sell the Luis

Muñoz Marín International Airport to private buyers after PREPA

threatened to cut off power over unpaid bills. Last July, PREPA

filed for bankruptcy.

The island’s unemployment rate is now

14.8% with a poverty rate of 45%. But the Puerto Rican authorities

have been under pressure from the US government to apply vicious

austerity measures. More than 60% of Puerto Rico’s population

receives Medicare

or Medicaid

services but the US has a cap on Medicaid funding for US territories.

This has led to a situation where Puerto Rico might typically receive

$373 million in federal funding a year, while, for instance,

Mississippi

receives $3.6 billion.

The austerity programmes imposed on the

Puerto Rican governments have meant taxes and fees went up on nearly

everything and everyone. Personal income taxes, corporate taxes,

sales taxes, sin taxes, and taxes on insurance premiums were hiked or

newly imposed. The retirement age for teachers was raised.

As the debt mounted, the US government

removed the power of managing and monitoring that debt out of the

hands of the Puerto Ricans and put into a new monitoring body,

PROMESA (The Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto

Rico) – a bit like how the EU governments took control of Greek

finances and provided bailouts with ‘conditionalities’ through

the EFSF and ESM. There is only one Puerto Rican on the PROMESA

board. PROMESA’s main aim is to service the debt, not restore the

economy.

What is to be done? Since it was

installed, PROMESA has begun outlining and implementing deep

government spending cuts. There is talk that the government should

pay back its bonds before providing essential services to its

citizens. Though repayment is still on hold, different classes of

bondholders are now locked in a legal dispute about which of them is

entitled to the revenue from the island’s sales tax, currently set

at 11.5%.

PROMESA wants the Puerto Rican

government to maintain a balanced budget for four consecutive years

and carry out significant privatisations of state assets. For Puerto

Ricans, that could mean austerity measures for the foreseeable future

imposed by an unelected body based outside Puerto Rico. As economist

Joseph

Stiglitz recently put it:

“The PROMESA

Board was supposed to chart a path to recovery; its plan makes a

recovery a virtual impossibility. If the Board’s plan is adopted,

Puerto Rico’s people will experience untold suffering. And to what

end? The crisis will not be resolved. On the contrary, the debt

position will become even more unsustainable.”

And yet the foreign bond holders do not

think this is enough and condemn PROMESA for being too weak. A group

of 34 hedge

funds that specialize in distressed

debt —sometimes referred to as vulture

funds—hired economists with an IMF

background. Their report called for increased tax

collection and a reduction of public

spending and wanted public

private partnerships and the ‘monetization’

(privatisation) of government-owned buildings and ports.

Another group goes even further. They

called on the US Congress to “consider a tax credit for U.S.

multinationals” and the “militarization of the island to provide

short to medium [term] security.” They want PROMESA closed down and

to be replaced by an “administrator who has broad authority to

execute contracts, coordinate with federal agencies and oversee

reconstruction.” The bondholders want more police and the US army

to enforce austerity. “The U.S. military needs to supplement the

15,000 Puerto Rican police officers to maintain law and order”,

while at the same introducing tax allowances at 100% of capital

expenditures “required to rebuild after Maria or build new

factories within a 2-3 year window.”

Another idea is for all the outstanding

debt to be incorporated into a ‘super bond’ that would get

interest directly from the tax revenues of the Puerto Rican

government. This plan would have a designated third party administer

an account holding some of the island’s tax collections and those

funds would be used to pay holders of the superbond. The existing

Puerto Rican bondholders would take a haircut on the value of their

current bond holdings. This is almost an exact replica of the private

sector involvement (PSI) deal that was imposed on the Greek

government in 2012 that led to a bailout of private bondholders and

the shifting of the bulk of debt onto the government books.

Is there any way out for the Puerto

Rican people or do they face permanent austerity and misery? One

solution coming from the left is for the US Federal Reserve Bank to

buy up all the Puerto Rican bonds at current market value and then

not impose any interest payment burden on the island. This is both

useless and utopian at the same time. Even if it were applied, the

debt would remain on the books and its servicing subject to the whim

of the Federal Reserve Board (and who knows who the Fed Chair would

be next year?). Moreover, if the Fed offers to pick up the bill, the

price of the bonds would rocket, enabling the ‘vulture funds’ to

make a killing at the US taxpayers expense. And it still does nothing

to solve the economic problem for the island that created this debt

in the first place. And, second, it is utopian because it ain’t

going to happen: the Fed will do nothing.

Clearly, the most effective immediate

answer is to cancel the debt. But that poses its own problems. First,

40% of the debt is locally held, often by local banks and pension

funds that could be bankrupted – so they would have to be brought

under the public umbrella. Second, cancellation would mean immediate

confrontation with the US authorities and the hedge funds – which

could lead to the closure of PROMESA and the imposition of a US

administrator to take over the government. In other words,

cancellation would mean a major political struggle on the island.

And what sort of Puerto Rican economy

is needed anyway? The model of a tax haven that encourages

multi-nationals to engage in transfer pricing scams has failed to

deliver incomes and jobs for those Puerto Ricans who have not left

the island.

Puerto Rico was an important hub, in

particular, for big pharmaceutical firms like Pfizer, which have kept

many of their investments on the island even after ‘936’ was

gradually ended. But Puerto Rico is no longer competitive in areas

where 75-80% of expenses come from payroll costs. Puerto Rico needs

to move up into higher-value manufacturing and services. It has a

large number of educated bilingual workers. There is potential to

turn the economy into a modern hi-tech service sector. But that would

require government investment and state-run firms democratically

controlled by Puerto Ricans. It’s the Chinese model, if you like.

Puerto Rico is a small island that was

exploited by the US and foreign multi-nationals with citizens’ tax

bills siphoned off to pay interest on ever increasing debt, while

reducing social welfare – all at the encouragement of foreign

investment banks making huge fees for doing so. Now Puerto Ricans are

being asked to keep on paying for the foreseeable future after a

decade of recession and cuts in living standards to meet obligations

to vulture funds and US institutions. And the troops will be sent

into ensure that! When it rains, it pours.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your thoughts...